The writer is an economist, anchor, geopolitical analyst

and the President of All Pakistan Private Schools’ Federation

president@Pakistanprivateschools.com

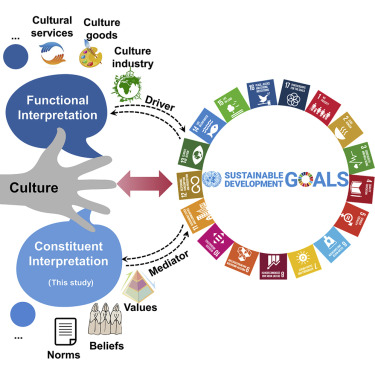

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a universal call to action to end poverty, fight inequality, and tackle climate change. However, there’s a missing piece in this puzzle – culture. International cultural relations can play a vital role in achieving the SDGs, but government-led initiatives addressing this connection are scarce. By harnessing the power of international cultural relations, governments can unlock new opportunities for sustainable development, social cohesion, and economic growth. It’s time to recognize culture as a vital component of the SDGs and work towards a more inclusive, equitable, and sustainable future. The absence of culture in the SDGs is a stark reminder of the challenges ahead. National governments’ reluctance to establish international commitments related to culture and diversity has hindered the inclusion of culture in the SDGs. Implementing, monitoring, and reporting the impact of international cultural relations pose significant challenges, including lack of data and metrics, limited resources, and complexity of cultural contexts. Even though international cultural relations can help achieve the UN SDGs, there are not many government-led initiatives that address the direct connection between the two. Why this absence came to be, highlighting the challenges to implement, monitor and report impact and progress of international cultural relations in general, as well as in the context of sustainable development. What policies, measurement frameworks, implementation methods or initiatives exist at the local, regional, national and multilateral levels? What can governments do to advance the connection between international cultural relations and SDGs, which is especially needed considering the current global context? Several factors contribute to this absence, including national governments’ reluctance to establish international commitments related to culture and diversity. There’s also a lack of sufficient leadership and consensus among governments, which hindered the inclusion of culture in the SDGs. Implementing, monitoring, and reporting the impact of international cultural relations pose significant challenges. These include: Lack of data and metrics, Inadequate data collection and measurement frameworks make it difficult to assess the contribution of culture to sustainable development; Limited resources and Insufficient funding and capacity constraints hinder the implementation of cultural initiatives; Complexity of cultural contexts and diverse cultural contexts and nuances require tailored approaches, making it challenging to develop universal policies. Despite these challenges, there are opportunities for growth: Cultural exchange and cooperation and International cultural relations can foster dialogue, understanding, and cooperation among nations; Economic benefits and Cultural industries can generate revenue, create jobs, and stimulate local economies; Social cohesion and culture can promote social inclusion, tolerance, and community development. Some notable initiatives and policies include: UNESCO’s Culture|2030 Indicators, a framework to measure and track progress in culture and sustainable development; The British Council’s cultural relations work which ocuses on education, arts, and culture to promote sustainable development and peace; Namibia’s sustainable tourism initiative which empowers local communities through cultural entrepreneurship and eco-tourism.

Five years remain until the 2030 deadline for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, yet the world is dramatically off course. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025, released in July, reveals that only 18% of targets are on track, nearly half show minimal or moderate progress, and close to one-fifth are stalled or regressing. More than 800 million people remain in extreme poverty, conflicts and climate crises are reversing gains, and inequalities are widening. In this bleak landscape, culture – long treated as ornamental – is increasingly recognised as a powerful accelerator of sustainable development. The MONDIACULT 2025 World Conference on Cultural Policies in Barcelona emphatically labelled culture “the missing SDG”, with UNESCO’s first Global Report on Cultural Policies (drawing on data from 196 countries and 116 cities) demonstrating that culture is still largely absent from national development strategies and Voluntary National Reviews. International cultural relations (ICR) – the deliberate use of cultural exchange, heritage cooperation, creative industries support and artistic diplomacy – represent one of the most underutilised levers available to governments and multilateral institutions. Yet the picture is far from uniformly optimistic. Progress remains fragmented, funding negligible, and geopolitical weaponisation of culture increasingly common. The global creative economy generated approximately US$2.3 trillion in revenues in recent estimates, equivalent to 3.1% of global GDP, and employs nearly 50 million people worldwide – more than the automotive industries of Europe, Japan and the United States combined. In some countries (Republic of Korea, Iceland, Nordic nations) the cultural and creative sectors contribute between 5–7.3% of GDP; in many developing economies the figure remains below 1%. These numbers are not merely economic. UNESCO’s Culture|2030 Indicators framework shows measurable correlations between investment in cultural participation, heritage protection and creative entrepreneurship on the one side, and advances in education (SDG 4), gender equality (SDG 5), decent work (SDG 8), sustainable cities (SDG 11) and peace (SDG 16) on the other. Despite lobbying by the #Culture2030Goal coalition, culture secured no standalone goal in 2015 and only four explicit targets (4.7, 8.3, 11.4, 12.b). The MONDIACULT 2025 conference acknowledged that this omission has had lasting consequences: culture appears in fewer than 20% of 2024–2025 Voluntary National Reviews. Official development assistance (ODA) for culture and recreation hovered at 0.3–0.5% of total aid throughout the decade – lower than funding for “recreational facilities” in some donor budgets. The Global South receives the majority of this meagre slice, yet it is overwhelmingly project-based rather than systemic. The return of hard-power rivalry has severely curtailed traditional cultural relations platforms. Russian institutions have been excluded from most Western-led programmes since 2022; Chinese Confucius Institutes face restrictions or closures in more than 20 countries; Iranian and Israeli cultural actors operate in almost complete mutual isolation. The ongoing destruction of heritage in Gaza, Ukraine and Sudan demonstrates that culture is often the first casualty of conflict – and one of the last to be rebuilt. While digital platforms theoretically democratise access, algorithmic bias and generative AI trained predominantly on Western datasets are accelerating cultural homogenisation. The G20 KwaDukuza Declaration of October 2025 explicitly warned of “new forms of digital colonialism” in the cultural sphere. As the 2025 ifa (Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen) study documents, most foreign ministries and cultural institutes still lack robust methodologies to demonstrate how a theatre co-production in Nairobi or a virtual heritage exchange between Brazilian and Indonesian museums contributes to SDG indicators. Without evidence, budgets remain vulnerable. Despite the grim backdrop, several converging trends create unprecedented openings: The 2025 conference secured commitments from more than 150 states to integrate culture into national sustainable development strategies by 2030 and to quadruple public investment in culture over the next decade – the strongest political pledge since the 2030 Agenda itself. Under South Africa’s 2025 presidency, culture achieved its most prominent G20 placement ever. The KwaDukuza Declaration, adopted unanimously in October, commits the world’s largest economies to treat culture as a cross-cutting priority in recovery plans and explicitly links cultural diversity protection to climate action (SDG 13) and inequality reduction (SDG 10). New platforms such as the BRICS Cultural Initiative, the African Union’s Great Museum of Africa project (due to partially open in 2028), and ASEAN’s expanding creative cities network are shifting the centre of gravity away from traditional North-South models. Initiatives such as the EU-LAC Digital Alliance for Culture and the UNESCO/Google partnership for virtual reconstruction of at-risk heritage sites demonstrate that technology can dramatically scale access. The British Council’s Cultural Protection Fund has already supported emergency digitisation in conflict zones from Yemen to Myanmar. Movements like Fridays for Future and global youth poetry slams have shown that cultural expression is often the most effective way to mobilise Generation Z on climate issues – a demographic that trusts artists more than politicians. The declarations of 2025 are undeniably the most ambitious ever adopted on culture and sustainable development. Yet the gap between proclamation and implementation remains cavernous. The same states that signed the KwaDukuza and MONDIACULT texts continue to allocate less than 1% of their national budgets to culture domestically, let alone internationally. The global North’s cultural institutes – while doing valuable work – still spend the majority of their budgets in Europe and North America rather than where the demographic and climate pressures are most acute. Moreover, the current model of international cultural relations remains uncomfortably state-centric at a time when civil-society and artist-led initiatives often prove more agile and trusted.

The risk is that “culture for the SDGs” becomes another top-down branding exercise rather than genuine empowerment of local cultural ecosystems. With only five years remaining, incrementalism is no longer defensible. States and multilateral organisations must: Quadruple ODA for culture by 2028, with at least 70% directed to least-developed countries; Make the UNESCO Culture|2030 Indicators mandatory for all Voluntary National Reviews from 2027 onward; Establish a new UN Special Rapporteur on Cultural Rights and Sustainable Development;?Launch serious negotiations for a standalone Culture Goal in the post-2030 agenda – the “SDG 18” that the world manifestly needs; Culture is not a luxury to be preserved after basic needs are met; it is the operating system through which human beings make meaning of every challenge we face. International cultural relations, properly resourced and imaginatively deployed, remain one of the few remaining tools capable of rebuilding trust across fractured societies; The declarations of 2025 have given us the roadmap. Whether we choose to follow it will determine whether culture finally moves from the margins to the centre of sustainable development – or remains, tragically, the goal we almost achieved. To advance the connection between international cultural relations and SDGs, governments can: Integrate culture into development policies to recognize culture as a key driver of sustainable development; Develop inclusive and participatory approaches to engage diverse stakeholders, including local communities, in cultural initiatives; Establish robust measurement frameworks to develop and implement effective metrics to track progress; Foster international cooperation to collaborate with other governments, organizations, and civil society to promote cultural exchange and cooperation. Despite these challenges, there are opportunities for growth. Cultural exchange and cooperation can foster dialogue, understanding, and cooperation among nations. Cultural industries can generate revenue, create jobs, and stimulate local economies. Culture can promote social inclusion, tolerance, and community development. However, the global landscape is complex, and the road ahead is fraught with challenges. The return of hard-power rivalry has curtailed traditional cultural relations platforms. The ongoing destruction of heritage in conflict zones demonstrates that culture is often the first casualty of conflict. Digital platforms theoretically democratize access, but algorithmic bias and generative AI trained predominantly on Western datasets are accelerating cultural homogenization. The declarations of 2025 are undeniably the most ambitious ever adopted on culture and sustainable development. Yet the gap between proclamation and implementation remains cavernous. With only five years remaining, incrementalism is no longer defensible. States and multilateral organizations must take bold action to quadruple ODA for culture, make the UNESCO Culture|2030 Indicators mandatory, and establish a new UN Special Rapporteur on Cultural Rights and Sustainable Development. Culture is not a luxury to be preserved after basic needs are met; it is the operating system through which human beings make meaning of every challenge we face. International cultural relations, properly resourced and imaginatively deployed, remain one of the few remaining tools capable of rebuilding trust across fractured societies. The declarations of 2025 have given us the roadmap. Whether we choose to follow it will determine whether culture finally moves from the margins to the centre of sustainable development – or remains, tragically, the goal we almost achieved.

Despite the challenges, there are opportunities for growth: Cultural exchange and cooperation and International cultural relations can foster dialogue, understanding, and cooperation among nations; Economic benefits and Cultural industries can generate revenue, create jobs, and stimulate local economies; Social cohesion and culture can promote social inclusion, tolerance, and community development.